Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 37:50 — )

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | iHeartRadio | Email | RSS | More

Good is the enemy of great.”

That’s how Jim Collins begins his classic business best seller, Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap… and Others Don’t. Collins argues the veracity of that sentence because people settle for good and stop pursuing better leaving us with good, but not great outcomes.

I don’t agree with Mr. Collins. Rather, I don’t know how you can possibly achieve greatness without first being good. Let me tell you why I don’t think good is the enemy of great!

The Value Of The Process On The Mountain

Mikaela Shiffrin is an 18-year-old World Cup Champion slalom skier. She was the subject of this month’s 60 Minutes Sports on Showtime.

Born in Vail, Colorado to parents who are both accomplished skiers, Ms. Shiffrin attended the Burke Mountain Academy in Vermont. Skiing conditions in Vermont more closely resemble those of the European ski circuit giving students experience and training that has produced 30 Olympians since it’s inception in the early 1970’s.

The Shiffrins sent their daughter to Vermont for training, not because they’re living vicariously through their talented daughter, but because she’s driven and committed to become world-class. She clearly has championship stuff as evidenced by her recent World Cup championship runs. Mikaela is the youngest slalom World Champion in U.S. history.

Jeff Shiffrin told 60 Minutes Sports that he and wife Eileen were not trying to produce a professional athlete. They simply wanted her to learn “the process.” Mr. Shiffrin talked candidly about the dance with the mountain. When you ski a good run that has five good turns in it, you immediately say, “That was fun. I want to do that again.” Mikaela’s parents concentrated on that dance while insuring she had fun learning the process.

The international skiing community marvels at Mikaela’s focus, especially given her young age. However, when you understand how her parents and her coaches have helped her, it’s apparent that they understood the value of repeating good habits. She wanted to be great so her supporters did everything possible to give her a process that would deliver consistently good results. That’s why they recommended she delay her competition.

On December 14, 2010 Mikaela won her first race. She was 15 and it was only her 8th International Ski Federation race ever! While other skiers were busy competing, she was busy training. Her coaches at Burke knew that a full day of competition would result in 2 ski runs while a full day of training would result in 15. Fifteen good ski runs a day over a prolonged period of time gave Mikaela the foundation to become a great world-class competitor.

Burke Mountain Academy has an old-style ski lift where skiers straddle a single seat, remain on their skis and a cable pulls them back up to the top of the mountain. Those riding the cable back to the top are mere feet away from the course watching other skiers navigate the gates. During a full day of training the skiers are never off their skis, even when being pulled back to the top. Skiers sit in quiet, solitary reflection on the ride back up to the top. No cell phones, no conversation with friends. Each student is alone with their thoughts as they watch other students ski down the course. The coaches credit the process for providing students with good focus training.

Mikaela is a training junkie who is known to spend up to 5 hours a day in the gym, when she’s not on the mountain.

When I was a J5 I did a lot of free skiing and I actually didn’t like free skiing. I just thought it was a waste of time and I would’ve rather been training or directed free skiing. I always wanted to be thinking of something, whether it was arms forward or my parents had a saying ‘knees to skis and hands in front’ – it’s been drilled into my head and every time I get on snow that’s what I start thinking. I did free ski a lot. I did do a lot of drills. It was probably 1/3 free skiing, 1/3 drills, 1/3 gates, and I did a lot of mogul skiing. I loved skiing the bumps, just the rhythm, trying not to eat it on a bump was really fun for me.”

By the time she had devoted herself to years of practice runs, gym training and other coaching, Mikaela was prepared to be great. None of it would have been possible without what her father calls, “the process.”

The Value Of The Process On The Gridiron

University of Alabama football coach Nick Saban is a man who constantly talks about “the process.” Saban brought an NCAA Championship to LSU in 2003. He’s coached the Crimson Tide to 3 national titles in 2009, 2011 and 2012. He’s the first coach in college football history to win a national title with two different FBS (Football Bowl Subdivision) schools. The man knows how to coach football.

Born in West Virginia, Saban learned the value of hard work as a boy. He’s a serious competitor who openly speaks about enjoying “the process.” Saban expects all his players to devote themselves fully to it. That means lots of time in the gym, in the film room and on the practice field, but it’s more than time. It’s doing things right. He expects every drill and every play to be done with 100% accuracy. Mostly, he preaches for his players to trust “the process.”

In a GQ article last September, a fellow coach made this observation about Saban:

The thing that amazes me about him is that he doesn’t let up,” says retired Florida State coach Bobby Bowden. “People start winning, they slack off. But he just keeps jumping on ‘complacency, complacency, complacency.’ Most coaches don’t think like that.”

Saban believes so strongly in “the process” that he won’t allow himself, his staff or his players to settle. Good isn’t good enough.

Saban’s guiding vision is something he calls “the process,” a philosophy that emphasizes preparation and hard work over consideration of outcomes or results. Barrett Jones, an offensive lineman on all three of Saban’s national championship teams at Alabama and now a rookie with the St. Louis Rams, explains the process this way: “It’s not what you do, it’s how you do it.”

The Value Of The Process Is In Consistent Details

It’s the little details that are vital. Little things make big things happen.”

John Wooden

You’re not likely a World Cup skier or an NCAA Division I head football coach, but the value of process is still beneficial to you. Details are an important part of “the process.”

That innocuous ski lift played a vital role in helping Mikaela Shiffriin learn how to focus. Her coach pointed out at least three benefits to that one seemingly minor detail. One, solitude. The skiers are alone in their thoughts. By going up the mountain alone the skiers weren’t able to engage in chit-chat with each other. Two, nearness to the course, watching other students ski the course as they rode back up to the top. Watching other students maneuver the course taught them how to make a better run their next time down. Three, by remaining on their skis the students weren’t able to use cell phones or do anything else other than remain on their skis focused on successfully making it back to the starting line of the course.

A small detail – an old-fashioned ski lift – accomplished big things for the students of this ski school. You can’t argue with “the process” of a ski school that has produced over 130 US Ski Team members and 30 Olympians. Don’t tell headmaster Kirk Dwyer that details don’t matter. And don’t tell him that a good process can’t produce greatness.

In Tuscaloosa, Alabama – home to the University of Alabama – part of coach Saban’s process has a name. Scott Cochran, Director of Strength and Conditioning, is a crazed Cajun who first joined Saban at LSU. NCAA rules are strict, limiting the exposure coaches have with the players. Enter the detail of the process which is part of Scott’s role. Spring drills and off-season conditioning is his domain. It’s such an important part of the Alabama football program that it has a name, “Fourth Quarter Program.” Alabama players are notorious for maintaining strength through all four quarters of a football game. Opposing players wear down during the game, but Alabama’s attention to “the process” prepares them to press on until the game ends. Do you need proof that it works? In their 2009 national championship season they outscored their opponent in the 4th quarter 121 to 32. In 2011, another national championship season, they outscored opponents 111 to 18.

3 Things To Help You Craft A Process Toward Your Own Greatness

Instead of relying on luck, or random chance, you should consider developing your own process. Don’t shy away from doing consistently good work, or doing as good as you can.

Allan Williams was the booking agent who booked the Beatles in Hamburg, Germany in August, 1960. He was unimpressed with them though and planned to replace them, hoping to land a better act. They weren’t yet great. It’s was suspicious if they’d be good enough to hang with the best acts of Hamburg, but they did the arduous work of grinding it out. It was part of their “process” required to prepare them for America and international fame. They remained in Hamburg from August, 1960 to December, 1962.

John Lennon was quoted in The Beatles Anthology…

We had to play for hours and hours on end. Every song lasted twenty minutes and had twenty solos in it. That’s what improved the playing. There was nobody to copy from. We played what we liked best and the Germans liked it as long as it was loud.”

Think of it. The Beatles weren’t even the best band in Hamburg at the time. Williams told them the competition was fierce. Namely, they had to watch out for the 900-pound gorilla band, Rory Storm and the Hurricanes.

You’d better pull your socks up because Rory Storm and the Hurricanes are coming in, and you know how good they are. They’re going to knock you for six.”

I don’t know what happened to Rory Storm and the Hurricanes, but it’s unlikely they stuck to the process. The Beatles developed a process, stuck with it and dug in to do the work. For over 2 years they appeared to languish in nasty, deplorable conditions (both living and playing), but there’s no doubt that without Hamburg the Beatles may have never been ready for America and world-wide fame. Hamburg was their process.

What are some things you can do to develop your process?

1. Take the time to devise the next step.

Don’t focus on the outcome yet. Greatness isn’t often the result of intense focus on the result, but on the process. Mikaela Shiffrin was making 15 ski runs a day while other girls were competing and making 2 runs a day. They were focused on competing. Mikaela was concentrating on her process.

What’s the very next thing you can do to move forward? The Beatles didn’t go from bad to great. First, they had to get good enough to entertain the tough crowds of Hamburg. What do you have to do to get good?

This step is likely going to involve lots of hard work. Don’t discount repetition. Howard K. Smith was a national news anchor for ABC News in the late 60’s through the mid-1970’s. I once heard him in an interview speak of training his children to be good communicators. He said every day he had them write one clear sentence. Such daily devotion to something so simple may have resulted in helping his son, Jack, become an award winning journalist before dying of pancreatic cancer.

Don’t complicate it. Don’t overthink it. Just figure out the next step and start doing it, consistently. Then you can figure out what’s next.

2. Do what others aren’t willing to do.

Alabama football players are willing to spend time in the gym while opponents are doing something else. Scott Cochran is running the team, cheerleading their weight room training and pushing them harder while opponents are calling it a day.

Mikaela Shiffrin was staying on the practice mountain in Vermont while peers were in Europe competing. She was in the gym doing lots of weight training while others figured they’d already done enough.

If you want to be great you must be willing to do more, go further and endure more than others. You can’t be good unless you’re willing to be above average. If everybody were good, then good would only be average. But as Sturgeon’s Revelation says (quoted from Venture, March 1958 by Theodore Sturgeon, American sci-fi author and critic)…

I repeat Sturgeon’s Revelation, which was wrung out of me after twenty years of wearying defense of science fiction against attacks of people who used the worst examples of the field for ammunition, and whose conclusion was that ninety percent of SF is crud.

Using the same standards that categorize 90% of science fiction as trash, crud, or crap, it can be argued that 90% of film, literature, consumer goods, etc. are crap. In other words, the claim (or fact) that 90% of science fiction is crap is ultimately uninformative, because science fiction conforms to the same trends of quality as all other art forms.

Sturgeon was surely onto something. Ninety percent of everything is crap. That means you’re going to have to work hard to unearth the things – the process – that will get you above the herd. If you don’t, you’ll end up as part of that 90%.

The Beatles were willing to leave home, go to Hamburg and live in squalor for over 2 years. They were just kids, but how many other kids were willing to make that sacrifice? Yes, they had talent, but we all know musicians that have marvelous talent who remain unknown. We’ve all heard the adage, “The harder I practice, the luckier I get.” Be willing to do the hard practice others aren’t willing to do.

3. Slow and steady will compound your results. Be patient.

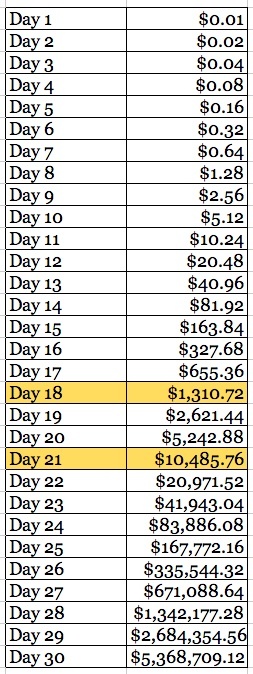

Did you take an economics class in college? If so, you may have had a teacher ask you if you’d rather have a penny doubled every day for 30 days or $1 million cash. The point of the question was to teach the power of compounding. Double a penny every day for 30 days and after a month you’ll have $5,368,709.12. Over 5 times the million bucks you’d have settled for if you selected the $1 million cash. But it’s just a penny. No, it’s a penny DOUBLED. Every day.

When you grind out the process the results pile up. And they keep piling up. They compound and they keep compounding.

As Malcolm Gladwell points out in The Tipping Point, there is a critical time when things seem to turn. If you look at the doubling of a penny every day, you won’t reach the thousand dollar mark until day 18. Over two weeks and you’ve not yet broken $1,000? That can be discouraging. But if you hang tough, by day 21 – just 3 days later – you’ve busted $10,000. Then on day 22, just one day later, you’ve doubled it (remember, we’re doubling it every day) to over $20,000. With only 8 days left you could quit, but you’d miss out on 99.61% of the total gain. You’d leave $5,347,737.60 behind if you quit too soon because you only gained .39% of your total results in the first 18 days. Greatness takes time. Don’t quit too soon.

Conclusion

My son is a pretty good hockey player. He was a little boy when we first put him on skates. Frustrated and angry, he wanted to quit, but my wife pressed him to hang with it. Because he couldn’t master it right off the bat, he wanted to quit. We encouraged him by convincing him that nobody can be accomplished when they start. So he fell. Often. Then he fell less often. He hung onto things and people. Until he no longer needed to hang onto anybody, or anything. And he continued to skate. And skate. And skate. Pretty soon he and his sister were always the best skaters every time we took them to the rink. By the time he was 11 he was as comfortable on skates as he was in sneakers. Today, he’s 33 and he can’t remember a time when he couldn’t skate.

Everything is hard, until it’s easy.

The key to success is to grind out the hard part until it gets easy. That’s best done when you can embrace and love “the process” without too much focus on the outcome. Enjoy those practice runs. Enjoy the weight room. Enjoy the spring training. Then, when it counts, you’ll realize you’ve paid the price for greatness.